MemCP is a high-performance, in-memory, column-oriented database.

Columnar storage means every column is stored as a contiguous array, which opens up compression opportunities that row-based databases cannot exploit.

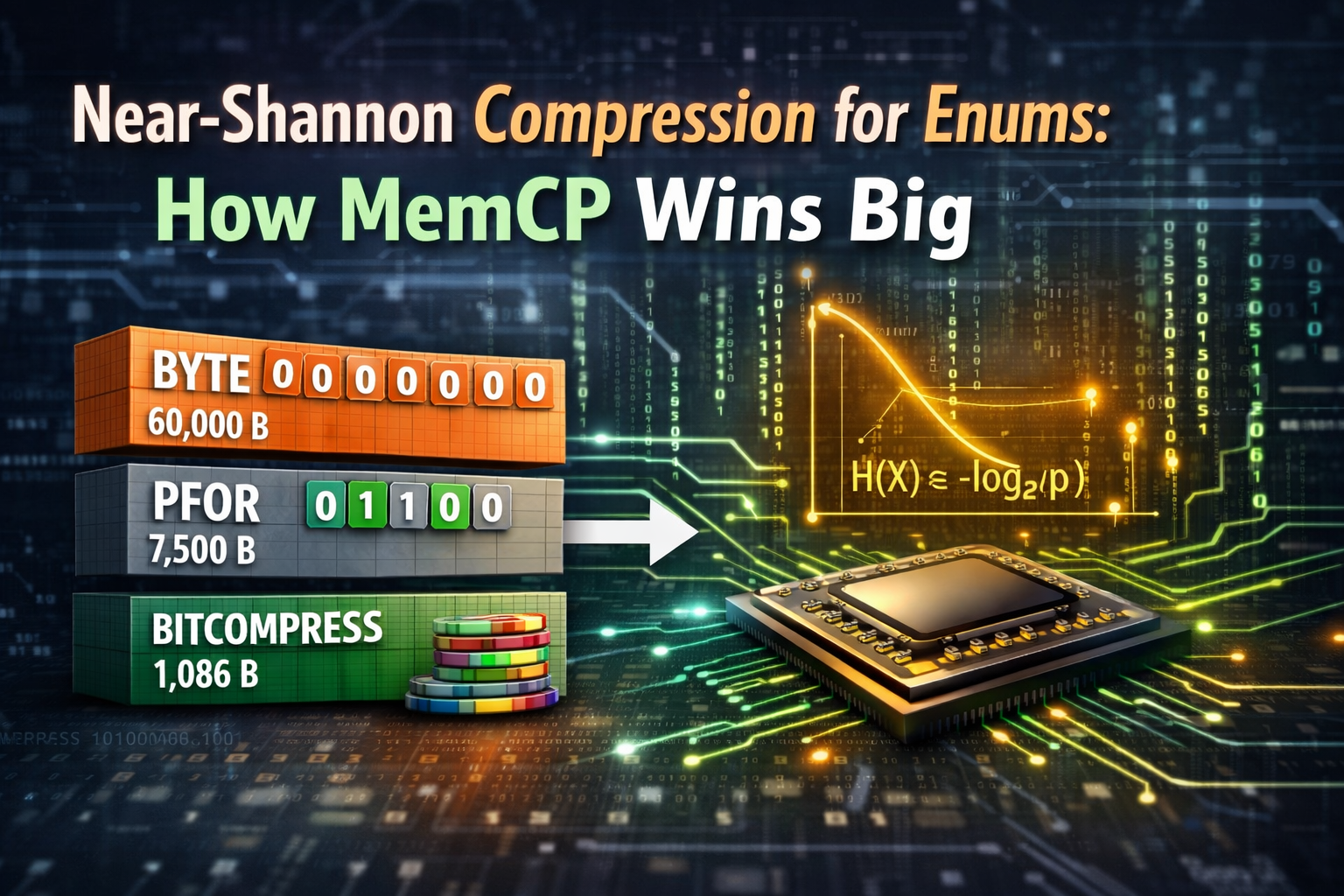

One of the most impactful cases is enum-like columns: booleans, nullable flags, status codes, categories — any column where a small set of values repeats millions of times.

This post compares three encoding strategies for such columns, using measurements from our microbenchmark suite running on an AMD Ryzen 9 7900X3D.

The Three Encodings

Byte Encoding (Traditional Databases)

The simplest approach: store one byte per value.

A MySQL TINYINT or BOOL column uses exactly this.

- Storage: 8 bits/element, regardless of distribution

- Access: O(1) direct array indexing

- Waste: For a boolean column that is 99%

false, 7.92 of those 8 bits carry zero information

For 60,000 booleans: 60,000 bytes.

PFOR Bit-Packing (MemCP old)

Patched Frame-Of-Reference packs each value into the minimum number of bits.

For k distinct values, that is ceil(log2(k)) bits per element.

- Storage: ceil(log2(k)) bits/element

- Access: O(1) with bit-shift arithmetic

- Improvement: A 2-value boolean column drops from 8 to 1 bit/element — an 8x improvement

For 60,000 booleans: 7,500 bytes (1 bit each).

But PFOR is blind to the actual distribution.

A column that is 99% false and 1% true still uses 1 bit per element, even though information theory says the optimal cost is only 0.081 bits/element.

PFOR wastes 12x the theoretical minimum.

Bitcompress: k-ary rANS (MemCP new)

MemCP’s new encoding uses rANS (range Asymmetric Numeral Systems), an entropy coder that approaches Shannon’s theoretical limit.

Instead of assigning fixed-width bit slots, rANS encodes each symbol with a cost proportional to its information content: -log2(probability) bits.

- Storage: approaches -sum(p_i * log2(p_i)) bits/element (Shannon entropy)

- Access: O(1) sequential, O(log n) random via 2-level jump index

- Key advantage: the rarer a value is, the more bits it gets; the more common, the fewer — automatically

For 60,000 booleans (99% false):

| Encoding | Size | bits/elem | vs Shannon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Byte | 60,000 B | 8.000 | 99x |

| PFOR | 7,500 B | 1.000 | 12x |

| Bitcompress | 1,086 B | 0.088 | 1.09x |

That is 55x smaller than PFOR and within 9% of the theoretical limit.

How Bitcompress Works

The codec operates on 8-bit precision.

The 256-slot interval [0, 256) is partitioned proportionally to each symbol’s probability.

A 99/1 boolean gets slots [0, 253) for false and [253, 256) for true.

Encoding packs symbols into a 64-bit buffer via modular arithmetic:

bufferx, rest = fastDivMod(buffer, width, invWidth)

buffer = (bufferx << 8) + lo + restDivision is replaced by multiplication using a precomputed inverse (Barrett reduction via bits.Mul64), making the hot path division-free.

Decoding extracts the bottom 8 bits to identify the symbol, then reverses the arithmetic:

slice = buffer & 0xFF

symbol = lookup(slice)

buffer = (buffer >> 8) * width + slice - loWhen the buffer would overflow, it is flushed as a 64-bit chunk.

A 2-level jump index enables O(log n) random access into the chunk stream:

- L2 (uint16): per-chunk cumulative element count, relative to L1 base

- L1 (uint32): absolute cumulative count every K chunks

This supports billions of elements while using only 2 bytes of index per chunk.

A sequential decode cache makes forward iteration O(1) per element.

Measured Performance

All benchmarks on AMD Ryzen 9 7900X3D, Go 1.24, -benchtime=2s.

Access Latency (60k elements, boolean 99/1 skew)

| Access Pattern | Latency |

|---|---|

| Sequential scan | 4 ns/elem |

| Sparse scan (50% density) | 9 ns/elem |

| Sparse scan (10% density) | 16 ns/elem |

| Random access | 674 ns/elem |

Sequential and sparse access — the dominant patterns in analytical queries (WHERE filters, aggregations) — are extremely fast.

Random access is slower because it requires binary search plus decoding within the target chunk, but this pattern is rare in columnar analytics.

Scaling: 1 Million Elements

The 2-level jump index scales cleanly.

For 1M booleans (99% false, 1% true):

| Encoding | Total Size | bits/elem |

|---|---|---|

| Byte | 1,000,000 B | 8.000 |

| PFOR | 125,000 B | 1.000 |

| Bitcompress | 14,270 B | 0.088 |

1 million booleans in 14 KB. That is 70x smaller than PFOR.

Sequential scan still runs at 4 ns/element — the same speed as at 60K.

The jump index adds only 2,934 bytes (1,379 L2 entries + 44 L1 entries).

Import/Export Throughput

| Operation | 5k elements |

|---|---|

| Import (encode) | 45 us |

| Export (decode) | 22 us |

Encoding is compute-bound (one multiply per element); decoding is faster because it avoids division entirely.

Where Bitcompress Wins Big

The advantage of entropy coding grows with skew.

Here is the compression ratio across different distributions:

| Distribution | Byte | PFOR | Bitcompress | Shannon |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boolean 50/50 (uniform) | 8.000 | 1.000 | 1.094 | 1.000 |

| Boolean 95/5 | 8.000 | 1.000 | 0.320 | 0.286 |

| Boolean 99/1 | 8.000 | 1.000 | 0.088 | 0.081 |

| 4-way 80/15/4/1 | 8.000 | 2.000 | 1.011 | 0.920 |

| 5-way skewed | 8.000 | 3.000 | 1.994 | 1.817 |

The pattern: the more skewed the distribution, the bigger the gap between PFOR and Bitcompress.

For the uniform case (50/50 boolean), Bitcompress is slightly worse than PFOR due to chunk overhead.

But real-world data is almost never uniform.

Nullable columns are overwhelmingly non-NULL.

Status columns cluster around a few common states.

Boolean flags are usually one value.

These are exactly the distributions where Bitcompress delivers 10-100x compression over PFOR.

The Sweet Spot: Low-Entropy Enums in Large Databases

Consider a production database with 10 million rows and a is_deleted boolean column that is 99.5% false.

| Encoding | Column Size |

|---|---|

| Byte (MySQL) | 10 MB |

| PFOR (MemCP old) | 1.25 MB |

| Bitcompress (MemCP new) | ~70 KB |

At 70 KB, the entire column fits in L1 cache.

At 1.25 MB, it spills to L2.

At 10 MB, it spills to L3 or main memory.

For an in-memory database like MemCP, this is not just a storage win — it is a speed win.

Less memory means fewer cache misses, which means faster scans, joins, and aggregations.

And because sequential decoding runs at 4 ns/element, the decompression cost is negligible compared to the cache-miss latency it avoids.

Summary

| Byte | PFOR | Bitcompress | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bits/elem (99/1 bool) | 8.000 | 1.000 | 0.088 |

| Compression vs Shannon | 99x | 12x | 1.09x |

| Sequential access | 1 ns | 2 ns | 4 ns |

| Supports skewed data | No benefit | No benefit | Massive benefit |

| Max symbols | 256 | any | 256 |

Bitcompress trades a small constant overhead on sequential access (4 ns vs 1-2 ns for uncompressed) for compression ratios that approach the theoretical limit.

For the skewed distributions that dominate real-world enum columns, this trade-off is overwhelmingly positive: smaller working sets, fewer cache misses, and faster end-to-end query execution.

The implementation is open source as part of MemCP.

Comments are closed